The COVID-19 pandemic has had devastating effects on the U.S. economy. As of May 26th, more than half of adults in households with children have experienced a loss of employment income since March 13th, and 40 percent expect a loss of income in the coming month. Falling incomes are having serious consequences, especially for households with children. In particular, food insecurity is soaring, with a third of households with children experiencing food insecurity—more than double the share from 2018.

Yet, to date, the most economically disadvantaged have been largely overlooked throughout the fiscal policy response to COVID-19. While congressional action has helped many people burdened by the pandemic, direct assistance has focused on stimulus checks and on replacing earned income for people who have lost jobs.

Indeed, the government sent out $93.7 billion in unemployment insurance (UI) benefits in May. But while these measures have been crucial for offsetting income losses for many people, the income support programs initiated in response to the COVID-19 pandemic have been less targeted to many of the households who were struggling to get by before the pandemic and who are continuing to struggle in this economic crisis. Individuals who did not file taxes in previous years may see a delay in any direct stimulus checks, and people who lack prior income are likely ineligible for unemployment assistance, leaving them out of the policy response.

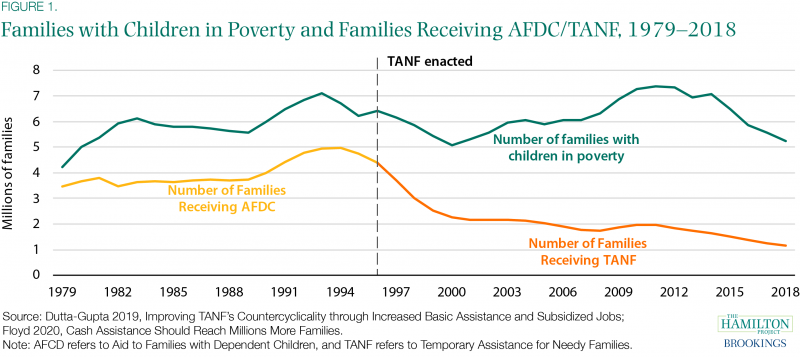

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, or TANF, is a block grant to states for cash assistance as well as child care, work supports, and other services for low-income families with children. It targets even lower-income families than UI, though eligibility varies widely by state. TANF replaced the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program, which provided direct cash assistance to low-income families with children. Since its enactment more than two decades ago, cash assistance makes up a much smaller share of TANF spending, and caseloads have plummeted, even while the number of families with children in poverty has remained high (figure 1).

Moreover, TANF no longer automatically responds to changing economic conditions. Under AFDC, states could access unlimited matching federal funds to subsidize their own spending, so funding automatically increased as need arose. By contrast, TANF’s block grant structure responds poorly to changing need, with a fixed amount of money going to states each year, regardless of need. And unlike unemployment insurance or SNAP, which ebb and flow with the economic situation, TANF programs do not receive more funds when more need arises.

While the program doesn’t automatically ramp up when economic conditions worsen, the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act provided a temporary $5 billion Emergency Fund in response to the Great Recession. In spite of this influx of funding, national TANF caseloads barely budged even as the number of families in poverty reached its highest level in decades (though some states expanded rolls). However, the emergency fund was successful in encouraging states to experiment with and swiftly implement innovative ways to subsidize employment. Thirty-nine states and DC helped place 260,000 low income adults and youth in subsidized employment.

So far during the 2020 crisis, there has been no congressional action to increase TANF funding. Moreover, states have inconsistently lifted work requirements and time limits, leaving many still subject to work requirements in a time when working outside the home creates health risks and, for some families, presents enormous challenges. The House-sponsored HEROES act would lift work requirements, but research shows that more can be done to make sure that the most vulnerable among us are getting aid proportional to need.

TANF affords great flexibility to states, but in many cases, cash-strapped states use that flexibility to spend TANF dollars on unrelated budget areas; only a fifth of TANF funds are used for basic assistance. Researchers argue that TANF funds need to be better targeted to ensure they are reaching those who most need them. In a 2016 Hamilton Project proposal, Marianne Bitler of the University of California, Davis and Hilary Hoynes of the University of California, Berkeley propose that states should be required to allocate at least 25 percent of TANF expenditures to cash assistance, at least 50 percent to core support (cash assistance, child care, and work-related activities), and all funds must be targeted to individuals and families below 150 percent of the official poverty threshold.

To make TANF more responsive to economic downturns, they also propose that TANF time limits, work requirements, and participation requirements be lifted when a state’s unemployment rate reaches 10 percent, a state qualifies for UI extended benefits, or an area meets other high unemployment indicators. As of May 31st, 47 states and the District of Columbia are eligible for extended benefits or have an unemployment rate over 10 percent.1

Beyond targeting, others argue that TANF funding can be increased and can be used more deliberately as a work support program. Indivar Dutta-Gupta of the Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality offers a Washington Center for Equitable Growth and Hamilton Project proposal that creates a TANF Community and Family Stabilization Program, which would expand TANF funding for basic assistance and job subsidy programs during economic downturns.

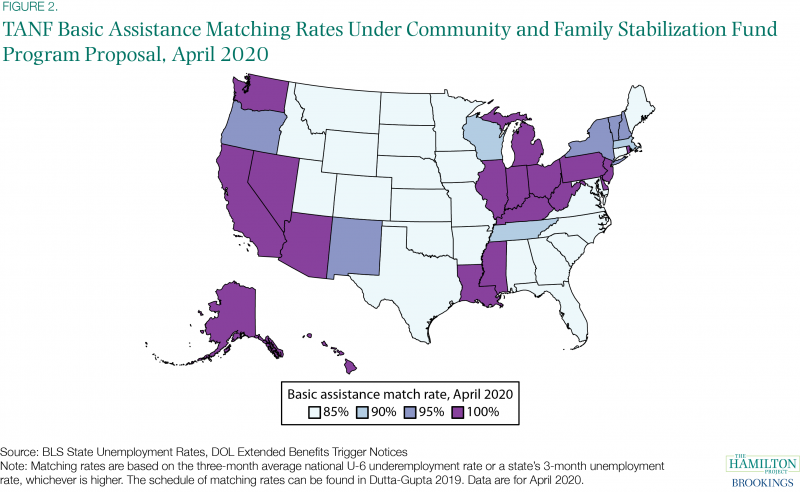

Key to returning countercyclicality to TANF, Dutta-Gupta proposes implementing a dual trigger method to link federal matching assistance from the Community and Family Stabilization fund to both national and state economic indicators. This dual trigger method allows for the program to respond to both national- and state-level economic disruptions. This design is ideal for our current economic situation, where we expect COVID-19 to have different economic effects on different states and at different times.

Nationally, the trigger is based on the three-month average underemployment rate (the U-6 unemployment rate), a broader measure of labor market weakness. For individual states, it is based on the three-month average unemployment rate. Dutta-Gupta’s proposal lays out a schedule based on the national underemployment and state unemployment rates for federal matching.

Figure 2 shows the basic assistance matching rate that states would receive from the Community and Family Stabilization Fund based on data from April 2020. Already, just one month into this recession, all states would qualify for an 85 percent match rate for basic assistance under the national trigger, and 26 states and the District of Columbia qualify for even higher match rates based on their state unemployment rates.

As states and localities begin the process of expanding allowable economic activity, the experience of the Great Recession shows that TANF-based job subsidies are effective at increasing employment. The subsidies would be available throughout the business cycle so that they could quickly be scaled up in times of economic need. Importantly, the job subsidies would include wraparound services such as child care, transportation, and job search assistance to ensure that employees are successful.

By making these reforms automatic, and based on economic indicators, the Community and Family Stabilization Program would give states a predictable source of federal funds. Past temporary expansions in TANF funding in response to downturns were less successful because states did not want to be stuck paying for higher levels of cash assistance when the emergency funds expired.

The reforms laid out by Bitler and Hoynes as well as the TANF Community and Family Stabilization Program proposed by Dutta-Gupta would target income and work supports to those most in need. Particularly as states begin to reopen, a TANF job subsidy could support increased employment among low-wage workers. Broad-based income support through both direct checks and unemployment insurance have been essential in limiting the income losses to tens of millions of American families during this crisis. Still, Hamilton Project authors show that more can be done to provide relief for families in need, with TANF as a key and underutilized part of the solution.

I am grateful to the valuable feedback from Lauren Bauer, Indivar Dutta-Gupta, Wendy Edelberg, Kali Grant, Sophie Khan, Kriston McIntosh, and Jay Shambaugh. I thank Emily Moss, Jennifer Umanzor, and Sarah Wheaton for their excellent research assistance.

[1]Nebraska, Utah, and Wyoming are the three states that do not meet either of these thresholds.