We estimate that U.S.-born employment increased by about 740,000 over the course of 2023. In contrast, the published data in the Current Population Survey (CPS) show a decline of 190,000. In addition, we estimate that the increase in employment among foreign-born people was 1.7 million, larger than the 1.2 million in the published data. Our higher estimates of employment stem from compelling evidence of recent population growth fueled by an unanticipated surge in migration that is not yet captured in official population statistics underlying the CPS. As we explain, the unanticipated surge has had implications for estimates of employment among both foreign-born and U.S.-born people.

In our previous work, we provided evidence that CPS data underestimated the recent increase in the civilian non-institutionalized population of people in the United States ages 16 and up (hereafter referred to as the population). That piece presented estimates of aggregate population numbers and employment growth that were larger than published CPS data. Our estimates of stronger employment growth are more consistent with the relatively strong employment growth in the Establishment Survey, which reports survey data collected from firms.

Here, we decompose aggregate population and employment growth into growth among the U.S.-born and among the foreign-born subpopulations. We find that the published data in the CPS significantly underestimate population growth from January 2023 to January 2024 and, thus, employment growth over the year for both groups. It is perhaps counterintuitive that measurement issues stemming from an unexpected surge in net migration would result in the underestimation of the growth in the U.S.-born population, but this is indeed the case.

Our methodology

To estimate foreign- and U.S.-born employment growth, we take several steps (for which we provide more detail in a forthcoming appendix.

- We begin with our previously published estimates of net international migration in recent years, which are consistent with published estimates from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO).

- We estimate how many non-institutionalized civilian U.S.-born people either turn 16 or die each year, which provides an estimate of a U.S.-born “natural increase” in the size of the population.

- We estimate how many non-institutionalized civilian foreign-born people either turn 16 or die each year, which provides an estimate of foreign-born natural increase. We add net international migration to that number to determine the overall increase in the number of foreign-born people.

- With estimated U.S.-born and foreign-born population growth in hand, we used published data on the employment-population ratio for each group to estimate growth in employment.

We show that published estimates of the size of the 16+ population, which were determined before the recent surge in migration was fully evident, reduce both U.S.-born and foreign-born employment numbers. Despite our simplifying assumptions that are detailed in a forthcoming appendix, reasonable alternative assumptions would generate the same conclusion that U.S.-born employment increased substantially over the course of 2023. For example, even if the published data on the employment-population ratio for the U.S.-born population slightly over or underestimate the true ratio because of changes in the composition of the population, our findings would still hold.

Published and authors’ population estimates

The CPS is a monthly household survey that is among the most valuable tools available to measure the strength of the economy. To produce aggregate statistics, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) uses previously determined measures of the size of the population, called population controls, in conjunction with real-time information from the sample of households about labor market activities. The population controls are determined in the prior calendar year based on carefully constructed projections from the Census Bureau; by construction they account for expected—but not unexpected—changes in the population. Therefore, the predetermined population controls do not update and account for an unanticipated migration surge such as the one we have seen in recent years. Here we use the latest available population information and find that the predetermined population controls understate population growth over 2023. We then use the updated population information to construct measures of aggregate employment, employment of U.S.-born people, and employment of foreign-born people.

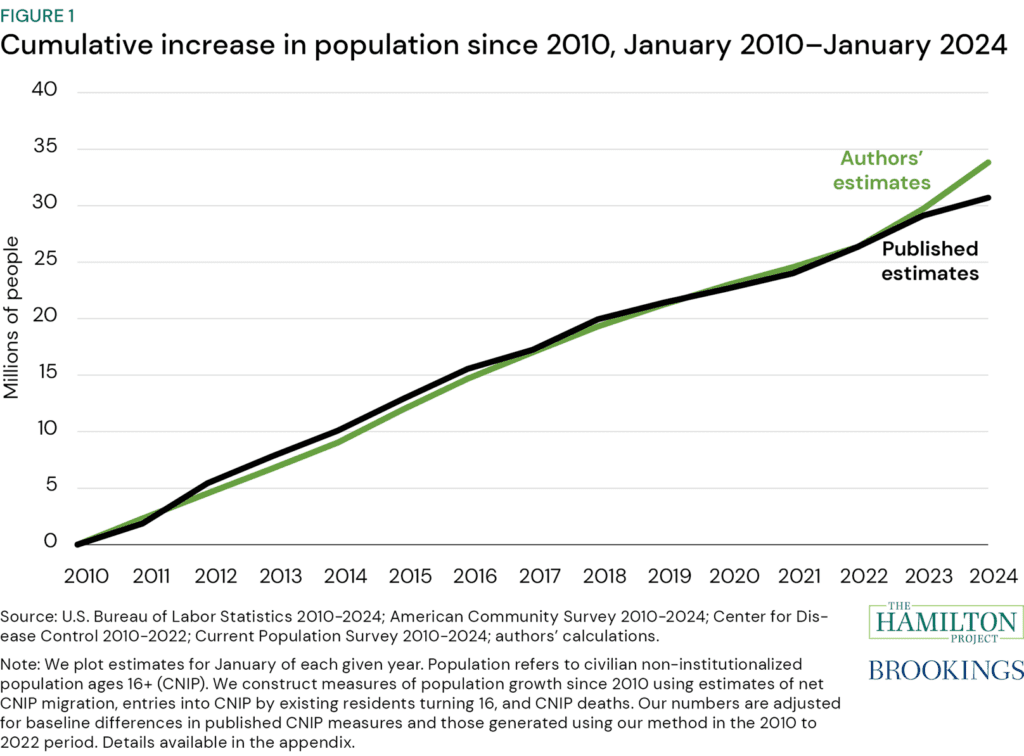

In our previous piece, we use CBO estimates of net international migration in combination with published death data and estimates of the number of people turning 16 to generate estimates of cumulative population growth since 2010. As shown in figure 1, our method closely tracks the pace of population growth through the end of 2022. However, mostly driven by a gap in estimated population growth in 2023, we compute that the cumulative increase in population since 2010 was about 3.1 million greater than in the published data. More precisely, we estimate that the increase in the population in 2022 was 600,000 greater than in the published data and the increase in 2023 was 2.5 million greater.

In this piece, we unpack our estimate of aggregate population to show our underlying estimates of the growth in the U.S.-born population and the growth in the foreign-born population. For those subpopulations, we assume the mortality rate is the same at each age for the U.S.-born and foreign-born, and that net international migration adds only to the foreign-born population. As shown in figure 2, we estimate that the cumulative increase in the U.S.-born population since 2010 was about 1.4 million greater than in the published data and the increase in the foreign-born population was 1.7 million greater.1

The difference in the recent growth in the U.S.-born population between CPS reports and our own estimates is particularly noteworthy. The published data show a decline in the U.S.-born population between January 2023 and January 2024. This is at odds with the fact that the number of U.S.-born people turning 16 in 2023 far exceeded the number of deaths in 2023. In contrast, our estimate is that the U.S.-born population increased by 1.5 million, a similar pace to the preceding year. See the box for an illustrative example of how an unanticipated migration surge can result in an underestimation in the number of U.S.-born people.

Box: Why do data issues from the immigration surge matter for estimates of the U.S.-born population?

While perhaps counterintuitive, the fact that unanticipated migration flows are not fully incorporated into the Census’ population controls yields published CPS population numbers that are too low for both U.S.-born and foreign-born. To explain how this is so, table 1 provides a simplified hypothetical: There are 100 people in the United States, and the country is experiencing population growth. Imagine that the estimated share of the population that is U.S.-born declines from year 1 to year 2, perhaps due to an influx of immigrants that is correctly reflected in survey data. This is shown in the first row of table 1. Although the numbers in table 1 are purely illustrative, CPS publishes such shares based on survey data, and indeed, the estimated share of the population that is U.S.-born fell between January 2023 to January 2024.

For the purposes of this toy example, imagine that the predetermined population controls accurately show that the size of the population was 100 in year 1. Then, in year 2, the population controls show the population rose to 102. But, the true size of the population in year 2 was 104 because of an unexpected increase in migration. With the “too low population growth” from the population controls and the accurate share of U.S.-born from the survey evidence, the U.S.-born population is estimated to have shrunk by 0.4 and the foreign-born population to have increased by 2.4. Instead, if the population controls had shown the “true” total population growth from 100 to 104, the U.S.-born and the foreign-born populations would both be shown to have increased. This can be seen in the bottom part of table 1.

In this way, the combination of a reduction in the share of the population that is U.S.-born and an estimate of population growth from the population controls that is too low can result in an estimate of a shrinking U.S.-born population even when the U.S.-born population is growing. This scenario accords with what we find to be true in 2023: The population controls are too low because of the unanticipated increase in migration, the share of the U.S.-born population shows a decline in the survey data, and the U.S.-born population is shown to have shrunk in the published data whereas we estimate that it actually increased.

Population shares

As it turns out, for reasons not illustrated in the toy example shown in the box, the predetermined nature of CPS population controls also affects estimated population shares of the U.S.-born and foreign-born. Though nativity is not explicitly incorporated into the controls, the population controls do include factors correlated with foreign-born status such as race/ethnicity and age. This indirectly affects the estimated share of the population that is foreign-born.

We use an alternative approach to estimate shares based on our preferred population estimates. The results suggest a greater increase in the foreign-born population share of the population than is suggested by the published data. Nevertheless, because this share is applied to a larger population number, it is consistent with the larger U.S.-born population and foreign-born population shown in figure 2.

Employment in U.S.-born and foreign-born population

The published data in the CPS show employment rates for both the U.S.- and the foreign-born population. We use the survey’s measures of the employment-to-population ratios to estimate employment based on our preferred measures of population, as shown in figure 4a.2 As highlighted in figure 4b, we estimate that employment among the U.S.-born rose by 740,000 in 2023, in contrast to the published decline of 190,000. We also estimate that employment among the foreign-born population rose faster in that year than in the published estimates, consistent with higher population levels. Figure 4a shows our employment estimates alongside those of CPS. The gold lines demonstrate how unusual it is to see a decline in U.S.-born employment when the labor market is strong. Previous declines in published CPS numbers were evident in 2010, in the aftermath of the Great Recession, and 2020, at the peak of the COVID-19 crisis. In contrast, labor market indicators were generally strong in 2023. For example, in the CPS the unemployment rate among U.S.-born workers never rose above 4 percent in 2023, and the official survey of establishments showed an increase of employment at nonfarm businesses of 2.8 million over the year. Our previous piece provides additional evidence that our estimates of greater population growth and employment growth relative to what is in the CPS explained much of the gap between employment in the CPS and the survey of establishments.

To be sure, the U.S.-born employment-to-population ratio is being held down by an aging population. However, the employment-to-population ratio for this group only ticked down from 59.1 percent in January 2023 to 59.0 percent in January 2024. Eventually, the aging of the population, coupled with reduced population growth from declining fertility, will cause the employment of the U.S.-born to decline. But this is not currently the case yet, despite the published CPS employment data.

The focus on population growth solves the puzzle: Because the U.S.-born population controls in the CPS shrank from January 2023 to January 2024, the CPS employment numbers among the U.S.-born also shrank over that period.

In figure 4b, we highlight the contrast between our estimates of 2023 employment growth and published estimates. As noted above, we estimate that the population grew in 2023 by 2.5 million more people than reported in the CPS. Because the CPS reflects survey data that point to an increase in the share of the population that is foreign-born, most of the 2.5 million people missing in the aggregate population turn out to be U.S.-born in our estimation: 1.6 million are U.S.-born and 950,000 are foreign-born. Given published estimates of the employment-population ratios in those two populations, we estimate that the increase in employment among the U.S.-born population was 930,000 greater than in the published data and employment among the foreign-born population was 590,000 greater.

Conclusion

Immigration will continue to play a key role in population and employment growth. We have suggested ways to successfully manage the economic gains from immigration, and The Hamilton Project has published a proposal to significantly improve the immigration system more broadly. Another consideration is the challenging impact of unanticipated immigration changes on our measurement of employment. We show here that correctly accounting for the recent immigration surge affects employment estimates for both the U.S.-born and foreign-born.

The long-run demographic trends in the United States are indisputable: Fertility is declining, and the population is aging. These demographic trends have implications for employment growth among the U.S.-born. Eventually, it won’t be surprising to see declines in U.S.-born employment even when the labor market is strong. But we aren’t there yet.

Our analysis suggests that after accounting for the recent unanticipated population surge, the growth in employment of both U.S.-born people and foreign-born people in the United States surpassed published estimates. Whereas published numbers suggest a decline in U.S.-born employment over the course of 2023, our estimates suggest that U.S.-born employment increased by 740,000.

The current episode highlights the need for timely population data in our statistical systems. The CPS and similar products play a critical role in helping policymakers make informed economic decisions, and it is essential that we continue to support and expand their capabilities.

Footnotes

- Our methodology constrains the estimates to be close to published data through January 2022, and then we use that same methodology to estimate population growth over 2022 and 2023. More precisely, we estimate that the average increase in the non-institutionalized U.S.-born population that turns 16 less those who have died is 1.6 million a year from January 2010 to January 2022. That estimate exceeds the published data for that period by 184,000. To account for that difference, we adjust our estimates for all years by that amount. Similarly, our approach underestimates the average growth in the published foreign-born population by 152,000; as a result, our methodology adjusts average growth for the foreign-born population by that amount. The result of those adjustments is that the cumulative increase in U.S.-born and foreign-born populations are the same in our estimates and in the published estimates through January 2022.

- We are using the published employment-population ratios, which is effectively a weighted average of that ratio across different demographic groups in the CPS. No doubt, the estimated composition of employment across different demographic groups would be different if the CPS fully accounted for the unexpected surge in migration. Although we expect that the implications are generally modest for the employment-population ratio and other shares in the CPS, such as the unemployment rate, we leave doing that important work to future research.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Kristin Butcher and Chris Foote for their insightful comments. Gabriela Campos, Olivia Howard, Eileen Powell, Quinn Sanderson, and Jonathon Zars provided excellent research assistance. Lastly, the authors would like to thank Jeanine Rees for the graphic design in this document.