Editor’s note: This memo was first published on econofact.org

The Issue:

American workers are often asked to sign away their right to work through non-compete clauses in employment contracts. Non-competes restrict a person’s ability to work for or to start rival firms, leaving workers with diminished bargaining power and fewer options for pursuing career opportunities. It is not only workers in high-tech or executive positions who are affected: non-compete contracts bind workers in a variety of occupations and at every level of education and wages. The conditions under which workers sign the contracts are often not conducive to a true negotiation, and may be contributing to a rise in employer market power and to depressed wage growth for American workers. Moreover, non-competes can limit entrepreneurship both for individuals and at the regional level.

The Facts:

- Non-competes are common in the U.S. labor market. A non-compete is part of an employment contract in which a worker pledges not to join or found a rival firm for a fixed period of time following the termination of employment. Two recent surveys have estimated that 16 to 18 percent of all U.S. workers are currently covered by a non-compete agreement. Non-competes are particularly common in technical fields and in executive positions. For example, research by one of us finds that 43 percent of engineers had signed a non-compete in the prior decade. Other researchers have found that 68 percent of CEOs at public firms report having entered into a non-compete. And slightly fewer than half of physicians (45 percent) are subject to a non-compete. Even low-income workers are affected: 12 percent of those with less than $20,000 in annual earnings and 15 percent of those with $20,000-$40,000 in earnings report having a non-compete.

- In principle, non-compete contracts could be attractive to both workers and firms. Limiting former employees from working for a competitor gives firms a way to protect trade secrets. But, in theory, workers could also benefit. For example, professional athletes may be willing to forfeit the right to jump from team to team in exchange for a lucrative, fixed-term contract. In addition, lower worker turnover resulting from non-competes might make firms more eager to invest in training their workers.

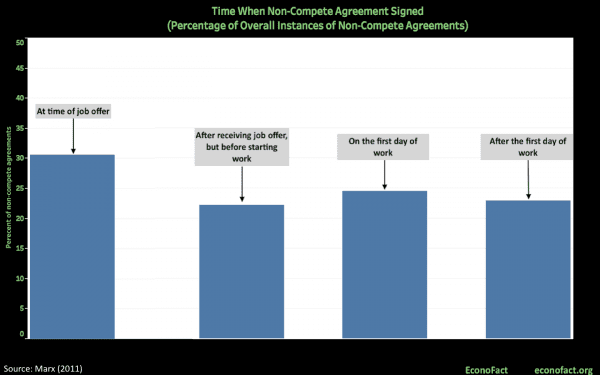

- But evidence suggests there is little negotiation of these non-compete contracts. Almost everyone who is asked to sign a non-compete does so; just 1 in 10 workers seeks legal counsel to review the contract. On its face, this behavior is not consistent with well-informed workers bargaining for compensation (also referred to as “consideration”) in exchange for costly limitations on their career flexibility. The timing of signing a non-compete agreement also limits an employee’s ability to negotiate for greater compensation: 70 percent of those with non-compete agreements were only asked to sign after receiving their job offer, and 47 percent were asked on or after the first day of work (see chart). Even when the non-compete agreement is presented to workers before the job offer is accepted, some workers might not be aware of the non-compete or its content, and may accept the contractual limitation without obtaining anything in return.

- Non-competes limit entrepreneurship, information flow, and worker mobility. There is evidence that non-competes lower overall job mobility, particularly for executives and workers in technical fields. There may moreover be ripple effects even on workers who have not signed non-competes. Along with diminished worker mobility comes diminished information flow: states with more stringent non-compete enforcement experience reduced dissemination of academic discoveries. Non-competes make it more difficult both for workers to found startups and for those startups to attract employees and scale up. Entrepreneurship is especially diminished within the industry of a departing worker, where a non-compete is most likely to bind.

- A worker does not need to have been sued by their former employer for the non-compete to have an effect. Non-compete agreements have been found to have a negative effect on job mobility, which cannot be explained alone by the few thousand lawsuits filed each year. Instead, even the possibility of legal action by one’s ex-employer produces a “chilling effect” on job mobility. Rather than risk a lawsuit, workers might stay with their current employer or switch industries entirely to comply with the contract. This “chilling effect” can occur even when the particular contract the worker signed is not technically enforceable in the state. For example, consider a state that allows non-competes of up to one year in duration, and suppose that an employer in that state requires its employees to sign non-competes that last two years and thus would not hold up in court. The average employee may not know about the one-year restriction, and probably will not have hired an attorney to explain the subtleties of the contract. To address this concern, policymakers have begun to ban firms from even asking workers to sign non-competes in some instances, rather than simply rendering them unenforceable in court.

- The way non-competes are enforced is important. When firms present workers with a contract that is not enforceable under state law, a handful of states invalidate the entire contract. This gives firms an incentive to write the contract in a way that conforms to state law (e.g., the contract might specify a term of one year rather than two). This is important because of the chilling effect of non-competes: especially stringent provisions can affect workers’ behavior even if they would not be enforced by a court of law. It is therefore notable that 41 states allow for some degree of after-the-fact judicial modification of non-compete contracts. This reduces the incentive to write contracts narrowly, given that the firm does not risk complete invalidation of the contract.

What This Means:

If it were the case that workers made fully informed decisions about signing a non-compete and could negotiate higher compensation in exchange for doing so, these agreements could be valuable for both workers and firms. However, the actual conditions under which non-competes are used provides reason to doubt that non-competes are indeed mutually beneficial in all or most cases. Moreover, even if a non-compete could be beneficial for an individual worker and her employer, it could still be damaging to the broader economy — for instance, if overall worker mobility and information spillovers decline. Current practices surrounding non-competes are often inconsistent with their use as mutually beneficial arrangements for workers and firms. This has negative implications both for workers’ careers and for entrepreneurship. Addressing these practices would require that state policymakers take a number of steps, as discussed in a recent policy proposal for The Hamilton Project. Informing workers about non-competes in advance of hiring, requiring that employers provide legal consideration in exchange for signing a non-compete, and disallowing the practice of ex-post judicial modification of non-competes are all possible directions for reform. Eliminating the most damaging uses of non-competes would help workers and employers to interact on a more level playing field.